Microchip Shortage Hinders Auto Production

Long-term Solution Might be at the U.S. – Mexico Border

By Nancy J. Gonzalez

Semiconductor chips are extremely important components of new vehicles for infotainment systems, dashboard displays, power steering and brakes, among other automotive systems. Auto parts can contain several sizes and different types of chips and just one vehicle needs between 50 and 150 microchips. However, the current semiconductor supply shortage remains an issue for the entire industry.

The supply pinch has hit auto manufacturers particularly hard because they are using many chips designed years ago that are lower-priority items for semiconductor makers. Those chips yield lower profit margins than the newer, pricier semiconductors that power 5G smartphones and video games, which are also in high demand worldwide and dominate many manufacturing lines.

The shortages have forced auto manufacturers to slash production in North America while some suppliers are also having trouble fulfilling orders. Many of the factors contributing to the shortfall are tied to recent events like the pandemic and the recent cold snap that slapped Texas and sidelined two chip factories in Austin as well as the growing demand of these components worldwide.

Audi recently announced it would reduce production at its San Jose Chiapa plant for its Q5 model to one shift due to the lack of semiconductor chips. Toyota cut production of its Tundra full-size pickup truck at its San Antonio plant.

Moreover, Nissan temporarily canceled production at two factories in the U.S. while the Aguascalientes Plant 1 stopped production for a while. Affected models included the Murano, Rogue, Maxima, Leaf, Altima, NV Vans, Kicks, Versa and March

General Motors and Volkswagen announced they were extending shutdowns or adjusting production schedules at plants in Mexico due to semiconductor chip shortages. Volkswagen de Mexico also adjusted its production schedule at its plant in Puebla for the Jetta model.

General Motors extended production cuts at three North American plants, including its facility in San Luis Potosi through the end of Q1. The GM factory in San Luis Potosi produces the Equinox, the Chevrolet Trax and the GMC Terrain SUVs.

“GM’s plan is to leverage every available semiconductor to build and ship our most popular and in-demand products, including fullsize trucks and SUVs and Corvettes for our customers. Our supply chain organization is working closely with our supply base to find solutions for our suppliers’ semiconductor requirements and to mitigate impacts on GM,” the company said in a statement.

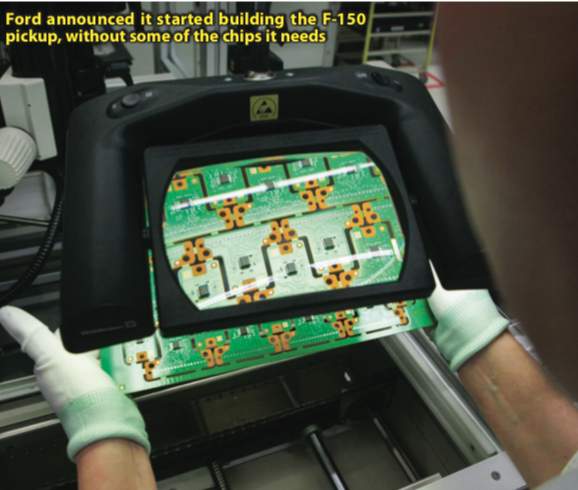

One of the automakers most affected is Ford. The company was forced to significantly cut production of its F-150 pickup, which is critically important to the company’s profits. Recently, Ford announced it started building the F-150 pickup, without some of the chips it needs. The automaker will park those unfinished trucks while they await the arrival of the missing chips, rather than shipping them to dealerships.

Consulting firm AlixPartners forecasts the shortage will cut US$60.6 billion in revenue from the global automotive industry this year. That conservative estimate includes the entire supply chain, from dealers and automakers to large Tier 1 suppliers and their smaller counterparts.

The global automotive industry is an extremely complex system of retailers, automakers and suppliers. The average automobile contains dozens of the integrated circuits, controlling air bags, power windows, catalytic converters and dashboard displays. As a result, the chip shortage is also affecting large suppliers such as Robert Bosch or Continental AG that source chips for their products from smaller, more-focused chip manufacturers.

“Although semiconductor manufacturers have already responded to the unexpected demand with capacity expansions, the required additional volumes will only be available in six to nine months. Therefore, the potential delivery bottlenecks may last into 2022,” said Continental.

An Answer in the Desert

Even though new semiconductor factories are among the most complex manufacturing facilities to build, costing billions of dollars and taking years to construct, some Asian companies are willing to take this opportunity and they are investing in U.S. communities near the Mexican border.

Last year, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC) announced a US$12 billion facility in Phoenix, Arizona. But recently, Asian media reported the investment might be closer to US$35 billion because the facility will be a “mega site” that would include six factories.

Construction on TSMC’s facility is expected to break ground this year and be operational by 2024. Once operational, the company will push out 20,000 wafers per month with a 5nm process with 3nm reserved for production in Taiwan.

TSMC is the world’s largest manufacturer of contract semiconductors and the company serves several industries. Moreover, TSMC produces 70% of the global auto industry’s supply of a key type of chip called a microcontroller, according to research firm IHS Markit.

Furthermore, Samsung has recently filed documents with authorities in Arizona, New York, and Texas, seeking to build a semiconductor fab, which is expected to create 1,800 jobs and cost US$17 billion. Samsung officials acknowledged that the company had not yet made a decision while exploring other potential locations and the fab could be online by as early as the last quarter of 2023.

Samsung already has a plant in Austin, manufacturing chips on 14 nanometer production lines, which has been operating for decades. This is its only chip-producing base in the U.S., and Samsung makes contract-based semiconductors for clients such as Tesla, Qualcomm and Nvidia.

Nowadays, some microchip manufacturing is done in Texas and Arizona. The Dutch chip company NXP owns and operates three wafer fabrication facilities in the U.S., two of which are in Austin, Texas, with a third facility in Chandler, Arizona. The representative products of these fabs include microcontrollers (MCUs) and microprocessors (MPUs), power management devices, RF transceivers, amplifiers and sensors. However, the recent cold snap in Texas knocked NXP’s two semiconductor plants in Austin offline.

A Major Incentive Might be on the Way

For years, chip industry executives and U.S. government officials have been concerned about the slow drift of costly chip factories to Taiwan and Korea. While major American companies such as Qualcomm Inc. and Nvidia Corp. dominate their fields, they depend on factories abroad to build the chips they design.

Recently, automakers joined chip companies calling for chip factory subsidies, and U.S. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and President Joe Biden both pledged to fight for funding.

Even though this package of legislation won’t solve the immediate auto-chip problem it is a step forward for the industry. The legislation might be discussed on the Senate floor during the spring.

The package includes matching funds for state and local chipplant subsidies, a provision likely to heat up competition among states including Texas and Arizona. Asian companies might be the major beneficiaries of this incentive.

In the longer term, a raft of U.S. companies is poised to benefit. Any chipmakers that build factories will source many tools from American companies such as Applied, Lam Research Corp. and KLA Corp. Furthermore, Intel Corp., Micron Technology Inc. and GlobalFoundries, which already have U.S. factory networks, will also likely benefit as well as smaller, specialty chip factories. Still U.S. companies must compete with low-cost Asian vendors in the long run.

Nevertheless, automakers will keep facing the chip shortage in the short-term and take decisions accordingly, which can affect jobs, or even increase the cost of a new vehicle.